Steve Dalkowski: The Final Chapter

(In the movie ‘Bull Durham,’ Nuke LaLoosh is based on Steve Dalkowski. He’s one of the major characters in my book, ‘High Heat.’)

After nearly making the Baltimore Orioles’ major-league roster in 1963, only to suffer a serious elbow injury before heading north with the parent club, Steve Dalkowski was never the same. His famed velocity was gone.

When Dalkowski struggled the next spring, the Orioles shipped him to Tri-Cities (Pasco, Washington), one of the lowest rungs in their system. Even though Tri-Cities manager Cal Ripken Sr. would become one of the standard-bearers for Dalkowski’s legend, he could only take so much of the left-hander’s antics. After Dalkowski hit a bar that the club had deemed off-limits, his career with the Orioles’ organization was over.

“I was the one who released him [from Tri-Cities],” Ripken says. “Yet there’s not a soul in the world who didn’t like him, including me. He just didn’t give himself a chance.”

After being released by the Orioles, Dalkowski signed with the California Angels and reported to their minor-league team in San Jose. He pitched only six games there, though, going 2-3. The Angels sent him to Mazatlán of the Mexican League in 1965. After being assigned back to the Mexican League for the 1966 winter season, he retired from baseball.

At loose ends, Dalkowski began to work as a laborer in the fields of the San Joaquin Valley in California. Places like Lodi, Fresno, and Bakersfield. He became the only fieldworker among the migrant workers. And during this time, he developed a new addiction to cheap wine -- the kind of hooch that goes for pocket change and can be spiked with additives and ether.

Dalkowski chopped cotton, dug potatoes, and picked oranges, apricots, and lemons. Along the way, he married a woman from Stockton. After they split up two years later, he met his second wife, Virginia Greenwood, while picking oranges in Bakersfield. But none of it had the chance to stick, not as long as Dalkowski kept drinking himself to death.

In 1991, the authorities recommended that Dalkowski go into alcoholic rehab. But during processing he ran away and ended up living on the streets of Los Angeles. “At that point we thought we had no hope of ever finding him again,” says his sister, Pat Cain, who still lived in the family’s hometown of New Britain, Connecticut.

On Christmas Eve 1992, Dalkowski walked into a laundromat in Los Angeles and began talking to a family there. They soon realized that he didn’t have much money and was living on the streets. The family convinced Dalkowski to come home with them. In a few days, Pat Cain received word -- her big brother was still alive. Soon he reunited with his second wife, Virginia Greenwood. and they moved to Oklahoma City, trying for a fresh start. But within months Virginia suffered a stroke and died in early 1994.

“That’s when I knew I had to get Stevie back home,” Cain says. “It was his only chance. He ended up in the hospital in Oklahoma City due to his drinking. I started to work with them to get him back here, back to New Britain. That finally happened in March 1994. That’s when he came home for good.”

Dalkowski moved into the Walnut Hill Care Center, near where he used to play his high school ball. And, slowly, Dalkowski showed signs of turning his life around. One evening he started to blurt out the answers to a sports trivia game the family was playing. Bill Huber, his old coach, took him to Sunday services at his Methodist church until Dalkowski refused to go one week. His mind had cleared enough for him to remember he had grown up Catholic.

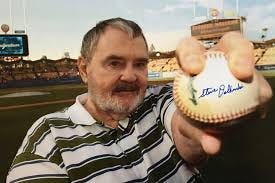

Less than a decade after returning home, Dalkowski found himself at a place in life he thought he would never reach -- the pitching mound in Baltimore. Granted, much had changed since Dalkowski was a phenom in the Orioles’ system. Home for the big-league club was no longer cozy Memorial Stadium but the retro redbrick of Camden Yards. On September 7, 2003, before an Orioles game against the Seattle Mariners, Dalkowski threw out the ceremonial first pitch. His friends Boog Powell and Pat Gillick were in attendance.

“I bounced it,” Dalkowski says, still embarrassed by the miscue.

Yet nobody else in attendance that day cared.

“He was back on the pitching mound,” Gillick recalls. “Back where he belonged.”

A few years later, in the sweet afterglow of the first warm day of spring, Dalkowski arrived at the St. George Church’s social center in New Britain. He had come for the Sports Hall of Fame Annual Induction Dinner.

Dressed in a mock turtleneck, gray pants, and dark blazer, he entered the room, taking slow steps, with his sister by his side. Without much fanfare, they found a table in the back row of the banquet room, one of the 27 under golden chandeliers trimmed with linen tablecloths and enough food, plates, and utensils to feed a small army.

Although Dalkowski and his sister didn’t leave their table, word soon spread that the pitching legend was in attendance. Throughout the evening, people dropped by to chat. When it was my turn, I asked Dalkowski what advice he would give for young pitchers.

“Throw strikes,” he replied. “And run. That’s good for the legs, you know.”

Then Dalkowski paused, ready to deliver the punch line. “And don’t drink,” he added, smiling.

A decade later, on April 19, 2020, Steve Dalkowski died in New Britain. He was 80 years old.

Dalkowski’s final days were spent in his hometown, in the company of longtime friends and high teammates. They believe, as many the game still do, that this left-hander was the fastest of the fast, the hardest thrower baseball has ever seen.

Very enjoyable column, Tim. I didn't know about Dalkowski and am glad to learn his story!